Gurkha Rifles Regiment

Among the many forces that tried to defend Johore and Singapore from the Japanese in early 1942, none carried a fiercer reputation than the Gurkhas Rifles. During the course of the Second World War, Nepal provided a massive proportion of its population to the Allied war effort: over 200,000 men served under British command against the Axis, on battlefields all over the world. Forty-five infantry battalions saw combat, and Gurkhas also manned transport, garrison and parachute units. In addition, 10 Royal Nepalese Army battalions saw service, mostly on garrison duty in India but some fighting the Japanese in the 1944-45 Burma campaign.

Tiger of Malaya includes two Gurkha battalions, the 2nd Battalion, 9th Gurkha Rifles and the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Gurkha Rifles. There’s also a “replacement” Gurkha battalion, representing an amalgam of survivors of the three other Gurkha battalions lost during the fighting farther north in Malaya.

The Gurkhas who fought in Malaya represented part of a long history of steady service. Nepal embarked on a militaristic course in the 1760’s, as King Prithwi Narayan Shah of the city-state of Gorkha in western Nepal conquered all of the Himalayan foothill region on the south side of the mountain range from Kashmir to Bhutan. All Nepalese warriors became known as “Gorkhas,” (usually rendered “Gurkha” in English, though 19-century writers often used “Goorkha” as well) from the name of Prithwi Narayan Shah’s city and the Gorkhali language they spoke. They surged through the mountain passes to conquer Tibet and impose tribute on the much larger kingdom, and struck southward into the fertile north Indian plain. Nepalese raids into British-protected Indian kingdoms led to war between Britain and Nepal in 1814. Two indecisive campaigns led to the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816, by which the Nepalese agreed not to attack Indian territory, and to provide troops to the British East India Company in exchange for hefty subsidies. Soldiering would provide an economic outlet for the poverty-stricken mountain villagers for the next two centuries.

The British called on their new allies a year later for the Pindari War, and Gurkha regiments served the East India Company for the next 40 years, most notably in the two Sikh Wars in 1846 and 1848. But the Gurkhas’ real test came in 1857, when Gurkha troops stayed loyal to the Company while Hindu and Muslim units rose in revolt against the Raj. As with the rest of the Indian Army that arose from the rebellion’s aftermath, the Gurkha battalions greatly expanded for the First World War and saw service far outside their traditional theater of war.

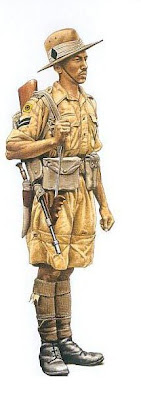

Gurkha units were trained and equipped along the same lines as Indian Army battalions, with one key additional weapon: the kukri. A kukri is a curved blade of excellent-quality steel, the traditional weapon of the Gurkha. The blade is very thick, and thus very heavy, imparting great force to a blow. They are worn as a set, with two small knives shaped just like the large one, kept in small sheathes on either side of the kukri’s scabbard. Both tip and edge are honed to razor sharpness, and the Gurkha uses it to both slash in a sideways motion, and to stab upwards under a taller enemy’s guard — and most enemies are much taller than the Gurkha.

All five battalions posted to Malaya in late 1941 were long-service units. But their first clash with the Japanese proved disastrous. Second Battalion, 1st Gurkha Rifles came forward on 10 December 1941 to protect the bridge at Asun near the Thai border from advancing Japanese columns. A Japanese tank-infantry force fell on them by surprise and crushed the battalion, with about 3/4 of its men lost. The remnants fell back along with 28th Indian Brigade, and continued to fight at reduced strength. But on 7 January they were overrun by Japanese tanks near Ipoh in northern Malaya and this time the unit was shattered. Among the survivors was Naik (lance corporal) Nakam Gurung, who along with 58 other Gurkhas led by Subedar Major Lalbahadur Gurung began cutting their way south through the jungle toward Singapore.

Malayan villagers helped the Nepalese with food and information, and they made good progress. But after about three weeks, Gurung came down with malaria. The Subedar Major (no relation) left the 12-year veteran in the wilds with a three-month supply of food and the firm belief that the Japanese would surely surrender before the rations ran out. The Naik recovered from malaria, yet the Japanese did not go away.

For the next seven years, Gurung remained in the jungle. Friendly Chinese villagers brought him food, and he trapped wild pigs and grew his own crops. Finally in 1949, a Gurkha patrol from the 1st Battalion, 10th Gurkha Rifles found him while pursuing communist rebels. He was awarded back pay, a pension, and medical treatment for seven years’ worth of terrible dietary deficiencies.

The Battle of the Slim River in early January destroyed two more of III Indian Corps’ Gurkha battalions. The two remaining battalions, 2/2nd Gurkha Rifles and 2/9th Gurkha Rifles, covered the British retreat and put up fierce resistance at Serendah in Johore, where they engaged in hand-to-hand fighting with troops of the Japanese 18th “Chrysanthemum” Infantry Division. Both battalions made it onto Singapore Island, and fought the Japanese aspart of 28th Brigade. Together with a Scottish unit, 2/2nd was the last Allied unit to lay down its arms.

Most Indian soldiers captured by the Japanese in Malaya and at Singapore joined the Japanese-sponsored Indian National Army which fought against the Allies in Burma. Gurkhas were also recruited; none joined the INA, remaining loyal to their oaths, and they suffered terribly in captivity as a result.

To reward this loyalty, the British government agreed to extend the £10,000 in compensation given to former British prisoners of the Japanese to Gurkhas as well — 68 years after the war’s end. Gurkha veterans are required to present written proof of their captivity to receive the award; most of the handful still alive are illiterate and few managed to claim the cash until Veronica O’Neal, the elderly widow of a 2/2nd British officer, found a roster hidden from the Japanese by her husband.

Comments

Post a Comment